The 9 Catapult Metrics I Used the Most For Football

One of the questions that I get asked the most when it comes to running Catapult, especially from new coaches who have just received their Catapult units for the first time is:

What exactly do you look at? Or more specifically, what metrics do you use?

This is a great question because one of the first things that you notice when you first start using Catapult is there are A LOT of metrics. There must be hundreds, if not thousands, of different data points and measurements.

Having access to all this data is awesome, but it can also be extremely overwhelming.

In my mind, one of the most important keys to success with using Catapult is cutting through the noise and figuring out what data is going to be useful for you, and then being able to implement an effective strategy that helps benefit your athletes and your team.

The metrics that I use the most fall into two main categories – Injury Prevention / Monitoring and Performance.

After using Catapult for six college football seasons, I’ve been able to really zero in on the metrics that help me be able to take sound actionable measures to help reduce our risk of injury and increase performance.

I’m always testing new things, whether it’s a new feature from Catapult or a formula I’ve put together myself. However, what I’m going to go over in this article are the numbers that have been most beneficial to me over the past 6 seasons.

Let’s dig into Injury Prevention and Injury Monitoring first.

Injury Prevention and Injury Monitoring Metrics

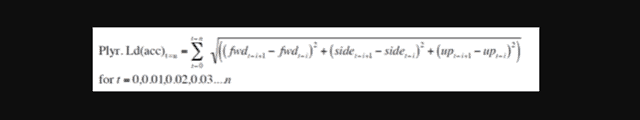

Player Load

The number one metric that I look at the most for injury prevention and return to play is Player Load. Player Load is Catapult’s signature algorithm and it’s the metric that they’re probably most known for.

Player Load calculates all acceleration and deceleration in three-dimensional space. In simpler terms, it measures how much work an athlete does in a training session.

Personally, I like to think about it in terms of how much gas is coming out of the gas tank of the athlete.

For example:

Athlete A and Athlete B both get in their identical 2021 Ford Mustangs. Athlete A drives 15 minutes across town and Athlete B drives 2 hours away to another city.

It’s pretty safe to say Athlete B is going to use more gas aka do more work and will have a higher Player Load because they traveled a much longer distance. Distance and Player Load are highly correlated.

If the distance covered is relatively similar then how they get there will play a big role in who ends up with a higher Player Load.

In this scenario, Athlete A and Athlete B are both driving from one side of the city to the other. Athlete A jumps on the highway, cruises a steady 55mph and exits to their final destination.

On the other hand, Athlete B takes city streets through downtown. They stop and start. Accelerate and decelerate. Turn and change directions. They do all of these things over and over again until finally, they reach the same destination on the other side of the city.

Anyone who has tracked their gas mileage (or ran short shuttles instead of jogging laps) knows that all of this stopping and accelerating over and over again is more work.

Having said all this, don’t make the mistake that you can compare athlete vs athlete, and whoever had the highest Player Load worked the hardest. This isn’t necessarily the case.

Movement efficiency, which I’ll discuss more in a few moments, comes into play which can cause some athletes to tend to have higher or lower Player Load than others.

For example, larger athletes are generally less efficient than smaller athletes.

You need to get an understanding of where each athlete’s baseline is before comparing against themselves and especially before comparing against other athletes.

Player Load in and of itself doesn’t really help with injury prevention. However, tracking and monitoring it over time is where it can become extremely beneficial.

Here are a couple of ways I do that.

Acute:Chronic Ratio

One of the most heavily researched Catapult formulas is the Acute:Chronic Ratio using Player Load.

Now, for every research article out there showing the benefits of tracking the Acute:Chronic ratio, you can find one saying that there is no correlation between the ratio and injuries.

I’m aware of both arguments, but for me, I’ve personally seen it be a very effective tool and so it’s something that we heavily utilize.

The Acute:Chronic Ratio compares how much Player Load the athlete has accumulated over a 7-day period (Acute) and compares it to what they’ve done over a 28-day (Chronic) period.

If this ratio becomes higher than 1.5 then that athlete is at an increased risk of injury. Depending on the study, it’s shown to be as much as 3x higher.

In other words, if they’ve done an average of one and a half times more work over the course of the past week than they have averaged over the past month, then they are at an increased risk of injury.

One reason I’m a big fan of the Acute:Chronic Ratio is that the concept just makes sense. If you do more work than what you’ve been preparing your body to do, then you might be setting yourself up for an injury.

The 7 to 28-day ratio is not set in stone. Some practitioners like to use a 7 to 21-day ratio. Personally, I use a rolling 7 to 28-day ratio that’s weighted toward the front end of both of those time lengths.

Tired of coming up with your own workouts? But don’t want to pay an arm and a leg?

I post workouts 5 days a week right here. (Did I mention they’re free?)

When to Use the Acute:Chronic Ratio

There are two situations where the A:C Ratio becomes a big focus of what we do.

First, for us for the sport of Football, it’s July through mid-August. This is when we plan out summer workouts and camp practice so that we don’t experience a huge spike in volume that can easily happen when football camp begins.

Football can go from running a few times a week in the summer to six days a week of challenging practices. This shift in schedule can lead to a giant increase in volume and Player Load. It’s one of the reasons I believe football as a sport sees such a high rate of injury during the first two weeks of camp.

The second situation where we pay really close attention A:C Ratio is with an athlete who is returning to play after an injury.

I work hand in hand with our Athletic Training staff to make sure that we progress each athlete back on a sound timeline.

Trying to do too much too fast can often lead to setbacks in the rehab process, or even worse, cause an overcompensation injury.

Like every metric we look at, the Acute:Chronic Ratio is not a holy grail and it’s not perfect. It’s a tool. It’s a tool that is used to help us gather as much information as possible to make the best decisions we can when it comes to the health and performance of each athlete.

Running Symmetry

One of the coolest things that Catapult measures is running symmetry. This is a relatively new metric that I’ve been really impressed by.

It will show you whether an athlete is favoring one side or the other when they are running in a straight line.

I use this metric all the time when working with our Return to Play athletes. All athletes are different, but if you have a baseline of where a particular athlete usually is, you can monitor them all the way back to their pre-injury symmetries.

It’s fascinating watching Catapult be able to pick up asymmetries that are almost impossible to see with the naked eye and then to watch those numbers go from favoring one side or the other sometimes as much as 15%, all the way down to under 1 or 2%.

Movement Efficiency

I use movement efficiency hand in hand with running symmetry.

Movement efficiency is the name I give to Catapult’s Player Load per Yard.

So, basically what this metric is telling you is, on average, how much player load does that athlete accumulate per yard covered.

Like most metrics, each athlete will have their own unique ‘fingerprint’ of how they move. Some athletes’ natural efficiency will be better than others. This number ranges from about .07 on the low end and I’ve seen as high as about .15 on the high end.

The key here is to look for when an athlete moves away from their norm.

When a .07 Efficiency Mover starts showing .1 or higher, then that is worth taking note of. It could be an indicator that the athlete has altered their gait because of, or compensating for, some type of injury. Tendonitis and shin splints are common culprits of Movement Efficiency being thrown off the norm.

Performance Metrics

The other batch of metrics that I use most often are our daily performance metrics. These are numbers that our Coaches receive on a daily basis and that I monitor to track our athlete’s response to cumulative fatigue.

Let’s talk about the numbers that I use with our Coaches (and players!) on a daily basis.

Daily Performance Report

Every off-season run, every practice, and every game our Coaches will receive a Daily Performance Report, broken down by position recapping the performances of each player in that activity.

The report includes the following metrics*:

- Player Load

- Acceleration Gen 2 B2-3 Total Efforts

- Acceleration Gen 2 B2-3 Total Distance

- Max MPH

- Sprints

- Sprint Distance

(*In the interest of total transparency there are a couple of metrics that I am leaving off)

Why have I chosen these numbers? Here’s a look at each one:

Player Load

We’ve talked about what Player Load does and how it’s recorded and even though it does have its flaws, it’s still a good indicator of how much work an athlete did that day.

Acceleration Total Efforts and Distance

I used to use Total High IMAs as a way to show Explosive Efforts on the field, but I kept running into issues where certain athletes would have particular movement qualities that would throw those numbers off and cause it to be a poor measuring tool.

So, I switched a few years ago to paying closer attention to accelerations.

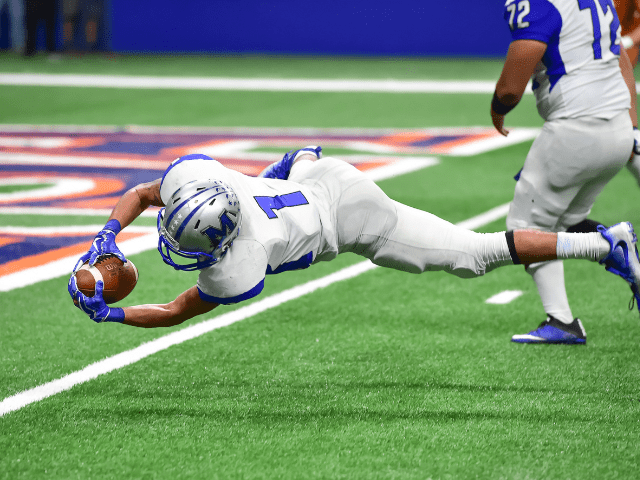

A high-speed acceleration usually involves a 3 to 4-step burst and a ‘3-step burst’ is something we reference a lot in our program whether it’s a 3-step burst on defense when the ball is declared or a wide receiver or tight end giving a 3-step (or sometimes 5 yard) burst when they catch a ball.

Accelerations made a lot of sense to focus on in so many ways and it’s currently one of my favorite metrics to look at.

Acceleration distance is exactly what it sounds like it is. It shows how long each athlete is able to hold those acceleration thresholds over distance.

Obviously, these two numbers are highly correlated, but I think looking at both is worthwhile.

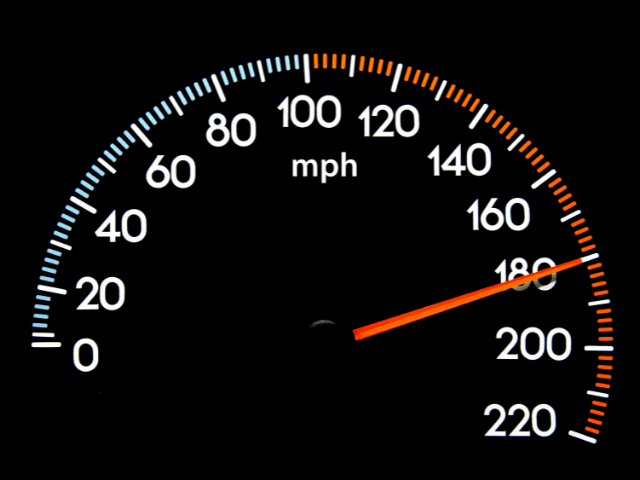

Max MPH

This is EASILY the favorite metric of both Coaches and Players, especially at first. What is the fastest an athlete ran in that session, that’s what Max MPH is giving you.

While it is really cool to see who ran the fastest on given practices or speed days and it does settle (and cause) many disputes, it’s probably the least useful number especially when you get in-season.

To hit a high MPH, you need BOTH ability and opportunity. If you don’t have the opportunity to really open up and sprint to full speed then you won’t end up with a high number. It does NOT mean you couldn’t have hit a high number, it just means you didn’t have the opportunity to.

Do NOT get caught up in trying to use Max MPH as a fatigue or performance indicator. It’s not, and it should not be used in this way.

Sprints and Sprint Distance

The final thing that goes on our performance reports are sprints and sprint distance. A “sprint” is classified at any time a player hits 14MPH and “sprint distance” is all of the yards that that player accumulates going 14MPH or faster.

Why 14MPH?

Honestly, when I first started using Catapult back at Elon six years ago, the default number that Catapult classified as a sprint was 12MPH. Given that 12MPH was not even 60% for some of our guys I bumped it up to 14MPH.

Totally an arbitrary number, but it’s one that I’ve stuck with ever since.

Can you use relative percentages instead of absolute numbers? Yes, and we actually look at both now. But, football is a performance-based game where you don’t get rewarded for just trying hard. You get rewarded for results.

So, as a player if you have to work harder to produce the same results as someone else, then so be it. That’s why we still use absolute numbers and not relative percentages.

Having said that, I do look at relative percentages when it comes to high-end sprinting in the neighborhood of 85% to 90%+ percent.

In order to keep the hamstrings prepared to run fast, they need to be running fast weekly so we do track and make sure guys are hitting high-end sprints at least a couple of times a week. And for many games, they’ll hit a few of these in the games themselves, especially if they’re on special teams, and that’s great.

From a performance and effort standpoint though, if you want to track who is flying around all over the field and giving great effort? Sprints and sprint distance are two great places to start.

Things to Keep in Mind

Position Demands

Once you get into practice, and this is true for ALL the performance metrics, be careful when comparing players of different positions or even players of the same position with different roles.

For instance, a slot receiver who is getting a free release will rack up more accelerations than an outside receiver who is getting consistently jammed off the line.

Don’t forget about special teams either. Have a Defensive End who plays on three special teams? Don’t be surprised when that player leads that position in basically every category every day.

The point is, be careful about passing judgment until you’re fully aware of the effect each position on the field within YOUR offensive and defensive schemes will have on each player’s numbers.

If you don’t understand the game of football, or whatever sport you’re using Catapult with, I highly recommend to start immersing yourself in the sport. Ask your Coaches if you can sit in on their film study sessions so you can learn the sport and the movement profiles of each position.

Online Strength Programs

- 1-on-1 Online Coaching

- Sports Performance Programs for Football, Basketball, Soccer & More

- Programs for Former Athletes (Legends) Who Still Want to Train Like Athletes

- Programs for Adults Who Want to Get Healthy (and look great at the beach!)

- Use Code “HB10” to Get 10% Off Today

Final Thoughts

There are hundreds and hundreds of data points with Catapult and knowing what to actually focus on is usually the first issue all of us run into.

The key is finding what you track, consistently, that will (or at least could) have a positive impact on player health and/or player performance. Once you’ve zeroed in on that, that’s half the battle right there.

Hopefully, this article has helped at least get you started down the path of figuring out what metrics you want to look at with your own program.